A drama has a progressive plot, an emotional climax, and a resolution. Consider your real life, everyday Joel Smith. Joel isn’t afforded such simplicity; there is no point A or B, no master plan, no carefully crafted screenplay. Realistically, he has a handful of vague anxieties that are never resolved by the end of the day. His life’s trajectory is orbital, revolving around a certain time and place with a group of people that may or may not stay constant.

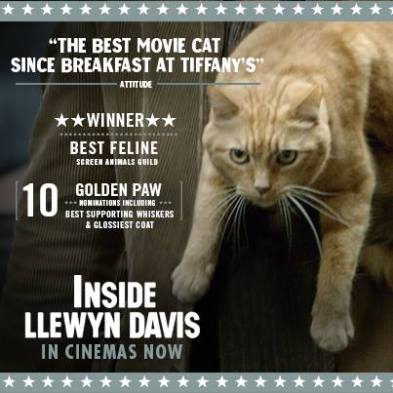

Inside Llewyn Davis (2014) is a bittersweet character study, one that truthfully embraces the cyclical, complex nature of life – in particular, one man’s struggle as an artist in an ever-changing musical landscape. Llewyn Davis represents one of many folk singers that sprung from Greenwich Village in the 1960s. With nothing but a guitar, a stray cat, and his name, Llewyn hits pitfall after pitfall, repeatedly caught in vicious cycles created both by ill-fate and his own crippling design. Llewyn’s self-destructive nature stems from his inherent selfishness and stubbornness to change; ironically, these traits are exactly what bind him to his integrity as an artist – Llewyn never “sells-out” or compromises his idealism for easy money. Little wonder the man scrounges for spare couches and mooches off his Village friends till they’re thoroughly fed up with him. Llewyn finds he possibly impregnated his former lover Jean behind her husband’s back, prompting her to demand an abortion and for the sake of womankind he wear “condom upon condom, wrapped in electrical tape” for like King Midas’ idiot brother, everything he touches turns to shit.

Yes, throughout the film, Llewyn is a dick. He compulsively lies to his friends and family, self-righteously gives himself credit, and acts condescendingly towards other’s musical performances. Why would anyone be invested in the journey of an inconsiderate scumbag? Despite his shortcomings, Llewyn is a sympathetic character; for every setback he tries doubly hard, for every unwanted pregnancy he arranges an abortion, he is selfish but admirably free-spirited. Witnessing Llewyn being constantly shut down made me hope that he find some affirmation, some shred of light to catch that elusive “happiness”.

Llewyn’s story is a loser’s story, but one worth mentioning because in the grand scheme of the film, his trials and tribulations feel like a journey towards redemption. It should be noted that the story takes place in 1961, a period in which America was mired in the Vietnam War, a lost cause that spawned anti-war protests, up to 3.8 million violent deaths, and countless lives forever ruined. If Llewyn’s story is one of redemption unfulfilled, what can possibly be said about the state of the American Dream?

Jean points out that Llewyn continually fails simply because he never plans for the future, accusing him of intentionally (perhaps masochistically) trapping himself in these vicious cycles. Their restaurant conversation clearly defines their separate philosophies:

Jean: Do you ever think about the future at all?

Llewyn: You mean like flying cars? Hotels on the moon?

Jean: And this is why you’re fucked.

Llewyn: No, it’s why you’re fucked. You just try to blueprint the future, move to the suburbs with Jim, have kids.

Jean: That’s bad?

Llewyn: If that’s what music is to you, a way to get to that place, then yeah, it’s a little careerist. It’s a little square, and it’s a little sad.

Llewyn’s brand of folk songs revolves around themes of death and dying (“Hang Me, Oh Hang Me”, “Fare Thee Well”, “The Death of Queen Jane”) – quiet dirges in lieu of his partner’s recent suicide. In many ways, Llewyn seems to be the last of his kind, unwavering in his determination to be true to his own artistic ideals despite his lack of a winter coat. His list of venues grows thin as his traditional folk songs fade into obscurity under a pre-Dylan, war-weary America.

The film itself is much like a folk song. Each verse represents a new story, a vignette, a window into an incident in the character’s life. The song journeys through each verse and by the end, repeats the chorus as they [the character] returns to their familiar situation, having changed. However, by the end of Inside Llewyn Davis, I wasn’t sure much had changed. The seamlessly identical intro and ending scenes frame the film, suggesting Llewyn remains a self-serving deadbeat without a couch.

This return to status quo, I contend, is entirely the point. Inside Llewyn Davis is uniquely “plotless”, nothing much happens – no dramatic climax, no resolution, and no affirmation whatsoever for the main character. The film is a tonal piece that’s simply going through the motions of a struggling artist existing solely on his music. The bookend suggests Llewyn’s life is cyclical in nature and the universe works in mysterious (often tragic) ways which we cannot predict.

But what about the damn cat? It’s strategically placed throughout the film, it must be a metaphor! It’s been mentioned before, but I do believe the cat represents Llewyn himself. Cats are instinctual creatures that are hard-wired to survive by any means necessary, yet they are vulnerable just as any house pet. It is said that cats have nine lives; do they live those lives with pleasure or pain? Llewyn accidently hits the stray cat with his car and glimpses the poor thing limping into the snowy darkness – a moment symbolizing not only Llewyn’s self-destructive nature, but also his tenacity to live. Perhaps Llewyn is continually cycling through his nine chapters in life; as a result, the film logically has no beginning or end.

In any case, I never imagined a seemingly hopeless film about a struggling folk singer could explore themes of rebirth, redemption, and fate with such brilliant subtlety. After processing and placing it in context of a grander scheme, I found Llewyn Davis much greater than the sum of its parts.